Itô's Lemma

Attention Conservation Notice

The 3rd post in a series of 5 in which the Black-Scholes-Merton Model for pricing European put and call options is derived.

- Brownian Motion as a Symmetric Random Walk Limit

- Stochastic Differential Equations & Geometric Brownian Motion

This follows Stephen Blyth's Excellent Book An Introduction to Quantitative Finance closely, with embellishment using python and some additional notes. This is probably:

- not very helpful if you pragmatically want to price an option

- overwhelming if you don't like math

- may miss some of the contexts you'd want if you have a lot of mathematical maturity

Now what?

In the previous post, we learned about stochastic differential equations and we derived geometric Brownian motion, a possible process for the evolution of a stock over time that has some reasonable assumptions:

Now that we have a form for , a good next step is to figure out the distribution of under the assumptions of geometric Brownian motion. To do this, we will need some additional tools, namely Itô's lemma.

Some Motivation

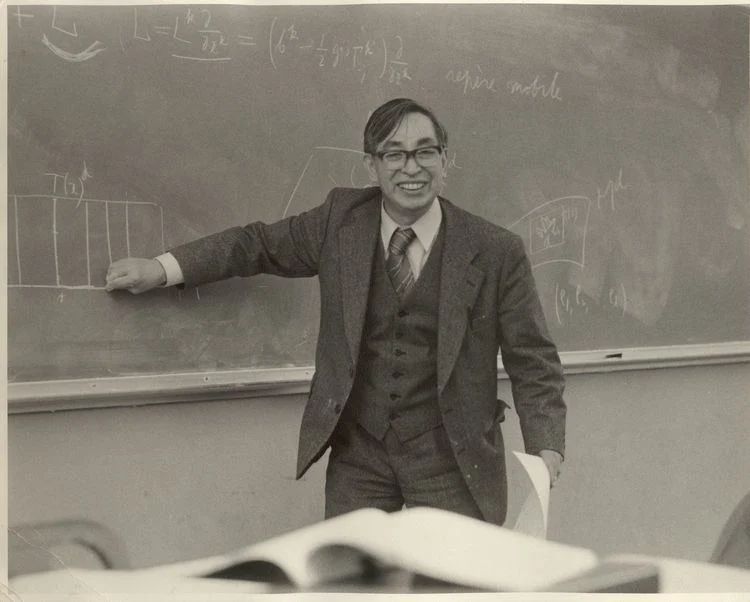

Kiyosi Itô in 1978

In the last post, we initially looked at the differential equation , where is the derivative of a Brownian motion (or a Wiener process) and are deterministic functions of time and the stock price at time , . From this we derived geometric Brownian motion, but let's consider the more general form for a bit.

To start, let's make this a simpler function. Suppose our stock price at time is given by the stochastic differential equation:

Then are deterministic functions of time (as opposed to non-deterministic functions of time and ) and we can write an integral solution like so:

Nice! We have the price as a weighted sum of integrals. We can't easily solve it in terms of , but we can get the mean and variance.

Since every has a mean of 0 (), , the integral of the drift function.

Similarly, since has a variance of 1 and are i.i.d., , or the integral of the variance of each step in the continuous random walk

This is all well and good, but what do you do when you have a more complex process that appears on both sides of the stochastic differential equation? Something like ?

We can't follow the same steps above. Instead, we want to rewrite as a function of a simpler process where takes the simpler form above. That is, , and .

Itô's lemma is used to find this transformation, and once we have that transformation we can find the mean and higher moments of the process (variance, skewness, kurtosis, etc). We will also see in a later blog post that this is very helpful for changing the underlying numeraire, which is a very useful technique.

Handy Dandy Taylor Expansion

Consider a function of and suppose that is deterministic and is twice differentiable.

Then taking the Taylor series, we get

+ ...

Now suppose that

,

Then

Since [1] and [2] then as and we have

Taking limits we obtain Itô's lemma

Itô's Lemma

With limits, we get

If , then we can substitute and get

grouping terms gives us the most well-known form of the lemma:

Itô's Lemma is easiest to remember in the following form: If then

where is defined by the identities

Plainly put, the derivative of a function of a random variable and time is a term about time, a term about the random variable, and a term reflecting the quadratic variation of the underlying Brownian motion (Wiener process). This final (memorable) form makes it much clearer that Itô's lemma is the stochastic calculus counterpart to the chain rule.[3]

Applied to Geometric Brownian Motion

Applying Itô's lemma to where follows geometric Brownian motion:

Let . Then

Applying Itô's lemma gives us

Thus, follows standard Brownian motion and is normally distributed. Specifically,

showing that under geometric Brownian motion the distribution of is log-normal.

We can use this information to temper our expectations about the next step in a stock.

In the plot[4] above, the

red

line is a geometric Brownian motion process with and . Thegreen

points are drawn from , showing a distribution of where the next point is likely to fall. We can see in this plot that almost every actual fell within the predicted distribution. It also kind of looks like a Christmas wreathExtra Notes

- Note [1][back]

For , .

- Note [2][back]

If is standard normal then , which has variance .

- Note [3][back]

Itô calculus extends classical calculus to stochastic processes via the Itô integral for adapted and semimartingale .

Financially, tracks the value of holding units of an asset whose price follows , highlighting why the chain rule analogy matters for hedging arguments.

- Note [4][back]

Make your own predictions with the same log-normal approximation: